By Michael Vasileff, Co-founder of Greenful Group (Greenful.com)

The war on textile waste is entering a new phase this year in the Netherlands with the implementation of the Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) Decree for textile waste on July 1, 2023. The Decree is one of the latest steps to deal with the Netherlands’ burgeoning textile waste crisis.

According to the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management, in a 2018 special study of textile waste (the latest data available), the Netherlands had 305,000 tons of discarded textiles, of which only 136,000 (45%) were separately collected (note, this includes only consumer textile waste, not industrial textile waste). The remaining 169,000 tons (55%) was either incinerated or sent to landfill as household residual waste. Of the amount collected, only 44,000 tons were recycled (=15% of total discarded textiles, primarily by recyclers outside the country). The remainder of the collected waste was almost all sent outside the country for disposal, sale, or reuse, mostly to third-world countries.

The 15% recycling rate is a very low percentage for a country that aims to be a leader in sustainability and the circular economy. However, it is in line with the overall European experience with textile waste, where more than 5,800,000 tons of waste is generated every year (European Environmental Agency), and only 15% is recycled or reused. Implementation of the new EPR Decree is the latest attempt to address this waste problem.

Background on EPR

The concept of EPR was first introduced over 30 years ago, and EPRs exist across many industries and waste streams, from mattresses and carpets to plastics and batteries. However, EPRs have recently become popular in the textile industry due to the explosion of waste resulting from the fast fashion trend. In 2008 the EU set its first Waste Framework Directive for textiles, and a 2018 amendment requires every EU Member State to have a separate textile collection program by 2025 at the latest. In 2022 the EU issued its “Strategy for Sustainable and Circular Textiles” framework, including a policy for “Extended Producer Responsibility.” The framework was designed to be implemented on a country-by-country basis. France was the first to adopt the policy in 2008, and in 2023 the Netherlands is implementing its own version.

What does the EPR do?

The EPR Decree of the Dutch Ministry of Infrastructure and Water Management does the following:

- Shifts responsibility for the collection of textile waste from the public authorities to the private producers of textile materials sold in the country.

- Requires producers to set up an appropriate intake system for the collection, reuse, and recycling of textile waste and the financing of the system.

- Producers must ensure that each consumer or end user of their product can hand in the clothing at a collection point free of charge when it is no longer wanted.

- Requires the sellers or producers of textiles on the Dutch market to report annually how much textile materials they have sold, how much is collected, and how much is recycled.

- Sets legal and enforceable targets on the market for how much textile waste should be reused or recycled, as seen below. Violations of the decree by producers are punishable by fines, penalties, or even possibly cessation of business activity in the Netherlands.

ObjectivesThe EPR for Textiles Decree holds producers/importers of textiles they release on the Dutch market accountable for separate collection, reuse, and recycling and for organizing and financing an appropriate collection system. |

by 202550% * reuse or recycling, of which:

|

by 203075% * reuse or recycling, of which:

|

* NOTE: these percentages are based on the total amount of textiles discarded by households, not the amount collected by municipalities or waste management companies

In effect, this decree completely changes the process of dealing with textile waste in the Netherlands. Whereas until 2023, municipalities and waste management companies collected textile waste from consumers, now the entire burden of collection and recycling is placed on the producers and sellers of that clothing. Furthermore, until 2023 collection was on a voluntary basis, where consumers chose to deposit their used clothing in collection bins. Now the Decree pushes producers to increase consumer collection rates to meet the target objectives.

In essence, this new approach says that the existing means of dealing with textile waste have not worked satisfactorily, now, it is the producers’ responsibility to figure out a solution. On the face of it, this sounds like an impossible challenge. How can clothing retailers figure out better waste collection and recycling methods?

The decree gives the producers some tools to deal with this situation.

How the EPR works in practice

The Dutch decree provides the following structure to help producers deal with this new challenge.

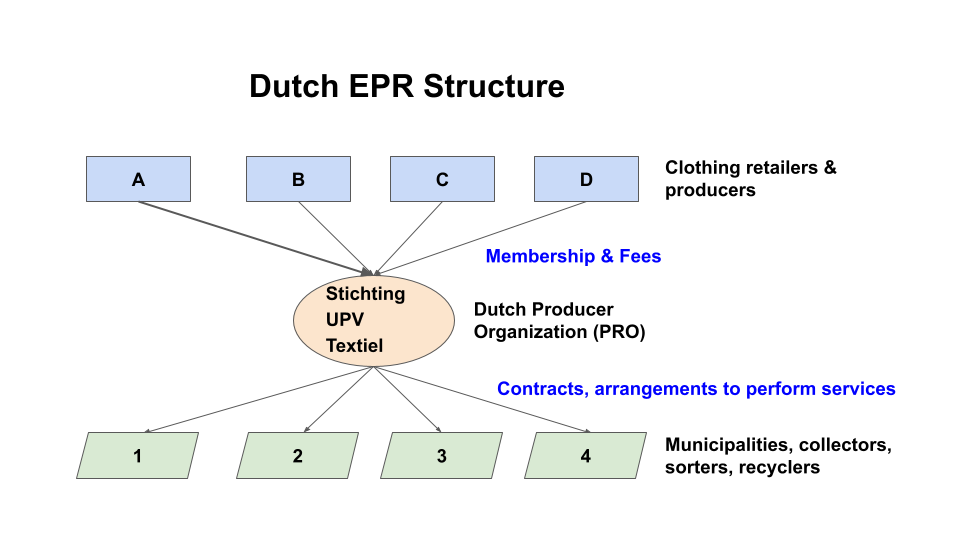

A. It sets up an industry producer organization (PRO),” Stichting UPV Textiel,” to act as the central coordinator of all collecting and recycling activities in the country on behalf of producers.

B. It gives producers the option to join this organization as a member. By joining, they “transfer” their responsibility as a producer to this entity. If a producer does not join, then it must deal with its own textile waste individually, which would be very difficult and expensive for any single company to manage.

C. When joining this organization, members agree to pay fees on each item of clothing they sell to finance the process. Stichting UPV has initially set the fee at Eur 0.03/piece of garment in 2024 rising to Eur 0.06/piece in 2025.

Note: According to Fashionunited.com, approximately 900 million individual garments are sold in the Netherlands annually, equal to 46 new garments per person. A fee of Eur 0.06/piece would result in total fees to Stichting UPV of Eur 54 million per year. In issuing the EPR Decree, the government estimated the total cost of implementing the EPR system at Eur 82 – 196 million per year.

D. The organization then uses this money to accomplish its mission under the EPR Decree. According to the UPV Textile website (https://www.stichtingupvtextiel.nl)

“the organization makes agreements with municipalities, collectors, sorters, thrift shops, and recyclers and cooperates with companies that develop new initiatives for collection and processing. This enables effective and affordable collection and processing of discarded clothes and textiles. In this way, companies do not individually have to make complex agreements with all the different parties. In addition, the collective enables investments in knowledge sharing and innovations necessary for achieving the targets.”

Analysis of the EPR, what does it do and not do?

First and foremost, the EPR can be considered only a first step in resolving the Netherlands textile waste problem and recognizing that prior waste collection methods did not work satisfactorily. The EPR with textiles is an attempt to try a solution that had mixed results in other industries. In another sense, the EPR can be seen as taking the waste problem off the shoulders of the government and putting it onto the industry, moving the problem from one place to another.

In relation to the primary goals of the EPR, the following can be said:

Goal 1: Bring reporting and accountability to the textile waste problem.

Here the EPR can make a large contribution to managing the textile waste problem by simply requiring producers, collectors, and other entities to report their volumes and other data. Surprisingly, there is a tremendous lack of information about the amount, types, sources, and uses of textile waste, so this is good progress. It should be noted that the EPR applies only to producers of clothing and household textiles; it does not apply to industrial producers of textiles such as carpets, curtains, upholstery for furniture, and others, which is estimated to be 15% of total textile waste.

Goal 2: Increase the level of collection and recycling.

While the EPR provides specific targets for the level of collection and recycling by 2030, it does not say how this should be achieved; that is left to the PRO to figure out. The EPR sets the reuse & recycling target for 2025 at 50%, whereas the 2018 figure was 15% (excluding waste sent to 3rd world countries). No current figures are available on the level of reuse & recycling in the Netherlands, nor on textile-to-textile recycling, but the figures are believed to be far below the target rates for 2025. In 2018 the reuse portion included sending the textiles to 3rd world countries, which is now seen as an undesirable alternative. Recycling includes making waste into cleaning wipers, car insulation, pressed fibers, and textile-to-textile recycling.

While there are penalties on individual producers for not achieving the recycling targets, it is not clear who is responsible when producers join the PRO. In this case, the producer has shifted his responsibility for collection and recycling to the PRO, what if the PRO misses the targets? Thus, by setting up a shared industry organization to implement the decree, it seems individual producers are let off the hook to meet collection and recycling objectives.

Goal 3: Incentivize a higher degree of circularity in the textile industry.

The EPR imposes additional costs onto retailers and producers to pay for the collection & recycling of waste as an incentive to improve the design and recyclability of their clothes. Yet if they join the PRO these costs, in the form of a fee per garment, are quite low. The additional Eur 0.06 fee can easily be passed along to consumers as a price increase. There is no other direct incentive or requirement on producers to increase the circularity of their clothing. For example, the Ellen MacArthur Foundation recommends producers also redesign clothing for easier recycling and include a minimum required percent of recycled material. None of that is included in the EPR decree.

An EPR system is only in use in one other country in Europe, France, where it has been in force since 2008. Here the results have been mixed. Since the establishment of the EPR in France, the number of collection points has increased from 16,000 to more than 46,000 in 2020, and the amount of collected waste increased from 2.7 kg/person to 9.7 kg/person. However, the collection rate is still only 34% of total discarded clothing, which is below that of other countries without an EPR, such as Germany and Belgium. The French recycling rate (as a % of discarded clothing) is also only 9%, which is below that of the Netherlands without the EPR. So it is clear that an EPR system is not the answer to all problems of textile waste.

Conclusion

The EPR does not address the two main challenges with textile waste.

(1) how to increase the collection rate (i.e., how to get more households to voluntarily place used clothes in collection bins), and

(2) how to increase the recycling rate of clothes when the tools and capacity are not currently available, especially for textile-to-textile recycling.

The EPR creates a framework of participants in the collection and recycling scheme: producers, collectors, recyclers, and others. The PRO is then responsible for coordinating all of these participants together to achieve the targets set by the government. While the PRO is given a budget and staff to face these issues, it still is faced with the same on-the-ground realities.

So much like in France, the new EPR policy is a step in the right direction but not the complete solution to textile waste that may have been hoped. Instead, more deep-seated issues concerning the commercial practices of producers, how consumers buy and dispose of clothing, and the industry’s capability to recycle used clothing, will determine our long-term success in stemming the avalanche of textile waste in Europe.

The Greenful Group recycles textile and plastic waste at scale into sustainable and recyclable construction materials. Greenful seeks to be a part of the solution for recycling all textile waste and works with partners in the industry to achieve this objective.