By Michael Vasileff, Co-founder of Greenful Group (Greenful.com)

One of the recent trends in the fashion industry today is to produce new clothes made with fabric reprocessed from textile waste, for example, recycling old cotton t-shirts into new cotton fabric. Several of the large retail clothing chains are pushing this alternative production method as a way of increasing sustainability in their business and becoming more “environmentally friendly.”

After all, textile waste is one of the biggest waste problems in the world. In Europe alone, over 3 million tons of textile waste is generated each year, while 85% of it ends up in landfills or is incinerated. In the United States, the figure is more than 15 million tons of textile waste per year, and in Asia is nearly double that amount, a staggering amount that is just going to get worse in the years ahead.

However, making new clothing out of old, used clothing is not the solution to the textile waste problem that some fashion industry leaders, and recycling companies, want you to believe. In fact, the textile waste problem is far more complex and harder to solve than they let on. Instead, we first need to fully appreciate what is in our textile waste and the limitations of fabric to fabric recycling before we can adequately deal with this issue.

A lesson on what is in our textile waste

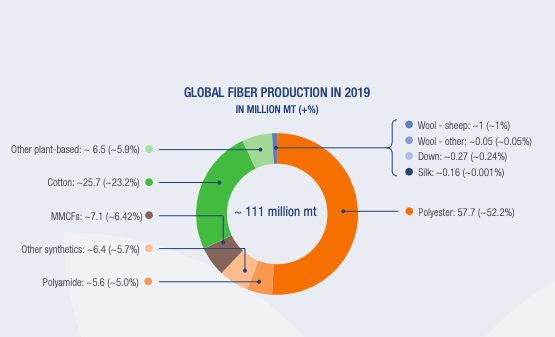

As reported by the Textile Exchange, a global non profit representing the world’s leading retail clothing brands and suppliers, more than 60% of the fabrics manufactured these days are synthetics like polyester (see chart), and only a minor portion are natural fibers like cotton or wool.

Chart from “Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report 2020”, Textile Exchange

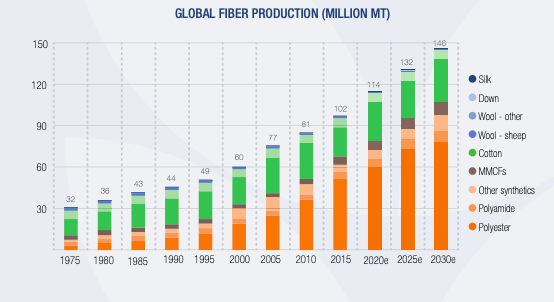

The proportion of synthetics is expected to increase over the next few years. By 2030, the Exchange projects the level of synthetic production to grow to more than 70% of all fiber manufactured. The annual volume of synthetics produced will rise from 70M tons to 100M tons (see graph) by 2030.

Chart from “Preferred Fiber & Materials Market Report 2020”, Textile Exchange

The reason has to do with the characteristics of synthetics like polyester. Polyester fabric is very low-cost to make, very durable, easy to work with, takes dyes well, and doesn’t wrinkle easily. Indeed, for large mass-market clothing retailers, polyester is a huge blessing. It is the wonder fabric that makes the trend-chasing “fast fashion” clothes possible.

On the other hand, natural fibers like cotton make up only a minor portion of the clothes we wear, representing 25-30% of the fabric manufactured globally. While natural fabrics are admired for their comfort and “organic” sourcing, they are usually more expensive to make, use significant natural resources to produce, and do not last as long as synthetic fabrics.

As it turns out, this difference in the types of fabric we wear has a huge impact on our ability to recycle them back into new fabric. Unfortunately, the fabrics we wear the most, like polyester, are the most difficult to recycle back into new fabric, and there is no easy solution on the horizon.

Recycling natural vs. synthetic fabrics

Cotton is 90% cellulose material, a naturally occurring polymer that is present to varying degrees in most plants. We are fortunate that the recycling technology for cotton is fairly advanced and works well, although the amounts produced are still very low, less than 1% of cotton waste is recycled back into the new fabric (the Ellen MacArthur foundation). Cotton recycling comes in two types, mechanical and chemical recycling.

In mechanical recycling, waste clothing is sorted and separated by color; only cotton items are allowed into the process. Machines are used to cut and shred the fabric into small pieces, which are then pulled apart into fibers. The recycled cotton is usually spun with another fiber, such as virgin cotton or polyester, to improve the quality of the yarn. The process results in reasonable quality new cotton fabric, although not as good as the original because the fibers are shortened. The color of the new fabric also depends on the color of the feedstock since the original dye remains in the fiber.

The other method for recycling cotton fabrics is the chemical process, which is the current star of the cotton recycling universe. In this process, clothing shreds are placed into large vats of chemicals that dissolve and separate the cellulose in the cotton material. The separated cellulose is then liquified and respun into the new cotton fabric (since cotton is 90% cellulose). A number of new companies are using this process now, but again the volumes are quite limited, currently an estimated 100,000-200,000 tons per year.

However, there are two issues with the current cotton chemical recycling technologies:

- there has to be a sorting and separation of the cotton clothing from the non cotton clothing before the chemical recycling is started, which significantly raises the costs of the recycling

- all of the non cellulose material that is separated out is disposed of as waste again and usually sent for incineration. Given the high amount of blended cotton fabrics, this can be quite significant

There is also new technology for cotton recycling that combines mechanical and chemical methods called a “soft mechanical recycling process.” This technology reduces the drawbacks of chemical recycling and improves the fiber quality over mechanical, but it still requires good sorting of material and relatively good condition of feedstock before processing.

With the proportion of synthetic waste only increasing over time, it is very unfortunate that the development of technology for recycling synthetics is far behind that used for cotton. There are several reasons for this.

It starts with the huge range of blended fabrics that we have, including polyester and cotton, nylon, rayon, viscose, and many others. Many cotton based clothes, such as jeans, also contain a synthetic fiber called elastane that provides stretch to the fabric and is difficult to recycle. Polyester clothes also have laminations or finishings made of plastics or other chemicals. This mix of types of materials in one piece of clothing means that it is difficult to mechanically or chemically recycle.

Mechanical recycling, involving the separation of fibers strands by machine and then reweaving of the fibers, leaves the polyester fabric weaker and of lower quality than before. This is why most recycled polyester clothing ends up as car insulation, carpets, rags, or some other type of non clothing product.

The Billie system of mechanical recycling of clothes

The chemical recycling of synthetics, much like cotton, breaks down the fabric into its constituent parts, in this case, the chains of polyester molecules, which are then recombined into new fabric. Yet the technology behind the chemical recycling of synthetic fibers is still not well developed. A number of companies are currently testing chemical recycling processes or coming into the pilot plant stage, but the volumes are far from making an impact any time soon.

Working against this new approach are two hard facts. First, virgin polyester fabric has historically been so inexpensive that recycling old polyester clothing into new has not been cost-competitive. This is not the case with cotton fabric which tends to be higher cost.

Second, the textile industry is also a victim of its own success in converting plastic bottles made from PET (a form of polyester) into polyester fabrics (think of Polar fleece fabrics). While the idea to take plastic bottles out of the oceans is good, it diverted attention and resources from developing processes to convert old polyester clothes into new polyester fabric. The result is that we solved one waste problem but forgot about another.

Chemical recycling of polyester

A question of volume

While we all hope these recycling technologies can advance quickly, the problem with textile waste is that we are running out of time. According to the Ellen MacArthur Foundation report “A New Textile Economy,” currently, only 12% of our textile waste is recycled in some way, and less than 1% is recycled back into new clothing. Thus, of the reported 50M tons of textile waste generated each year globally, only a very small portion is actually recycled “textile-to-textile.”

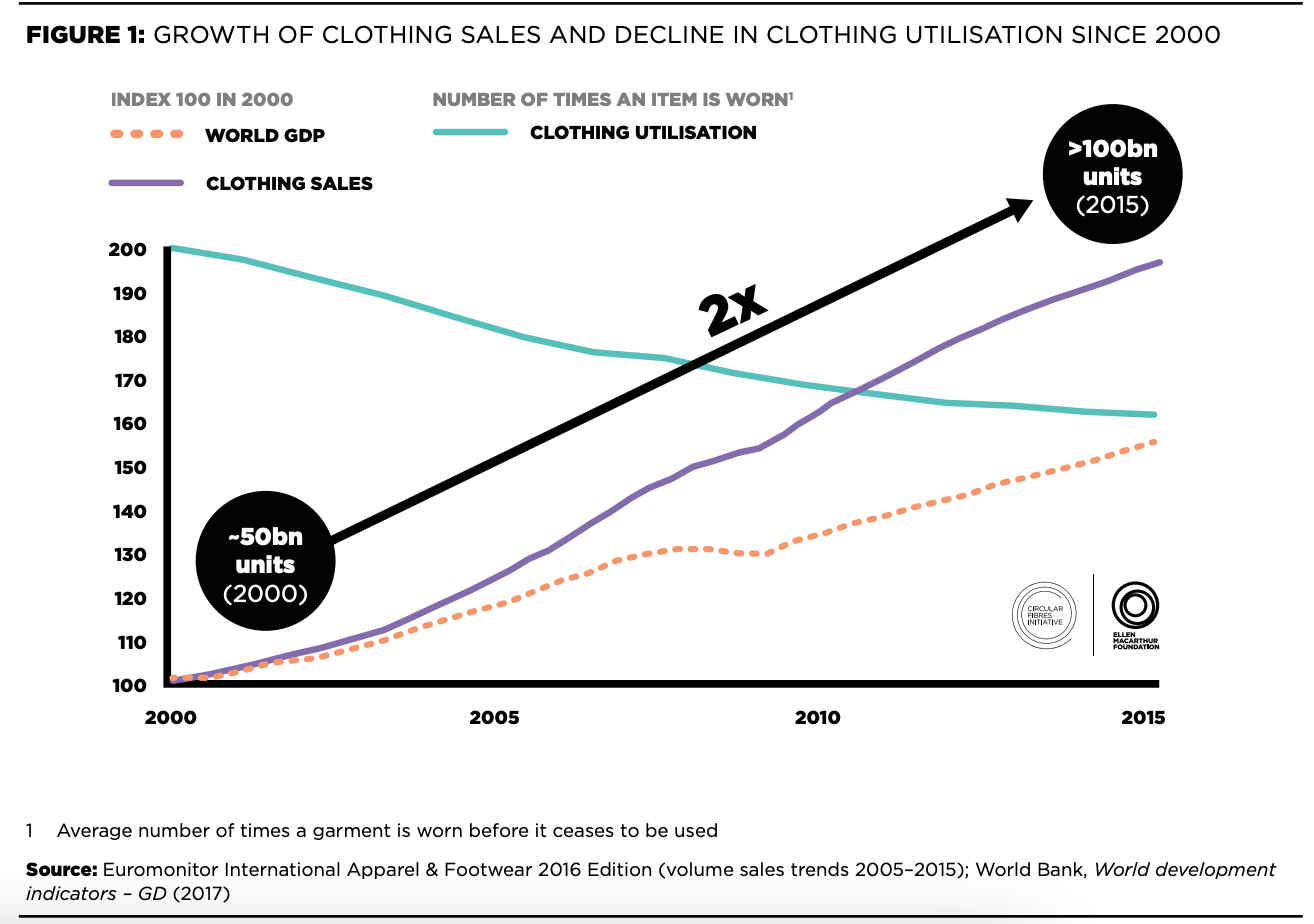

The bad news is that the situation is only going to get worse. The MacArthur report continues that the number of garments sold globally doubled from 50 billion units in the year 2000 to 100 billion units in 2015. At the same time, the rate of “utilization” (the number of times a garment is worn) has decreased by 36%, a figure which looks likely to grow due to the global spread of the “fast fashion” trend. The report adds that sales of garments worldwide are expected to triple in volume by the year 2050. This means that a virtual mountain of textile waste is coming our way in the years ahead, based on current trends.

The implications for the clothing industry are fairly stark. If the industry aims to achieve full textile-to-textile recycling within the next 2-3 decades, it has a lot of catching up to do. Mathematically, the industry would need to increase its recycling level by more than 100x today just to match current waste levels. However, the level of textile waste is a moving target. Textile-to-textile recycling volumes would need to triple again in size to meet waste growth of just a few years out. Given that the vast majority of the waste is synthetics, for which currently there are no adequate recycling solutions, it would seem nearly impossible to achieve full textile-to-textile recycling in the foreseeable future.

The MacArthur report recognizes this point and proposes a radical rethink of the textile and clothing industry’s business model. This includes changing the way clothes are designed to be more recycle-friendly, changing the way clothes are sold, encouraging higher customer utilization rates, and improving recycling methods. Taken together, these proposals bluntly call for a complete change in business methods and a sharp departure from the “fast fashion” business model. This is a huge challenge for an industry that built its fortunes on fast fashion.

Instead, the real solution to textile waste lies outside of the textile and clothing industry, finding uses for the waste beyond fabric to fabric recycling. The MacArthur report does the industry a disservice by focusing only on internal industry solutions to the textile waste problems. While it is clear that the textile and clothing industry must reform itself to become more circular, not all of the textile waste solutions need to come from within the industry itself. As seen earlier, the dynamics of the industry and limitations of current technologies make full fabric to fabric recycling an unrealistic dream.

Rather the textile industry should be looking outside its own walls and working with partners in other industries to help solve the issue of textile waste, for example, by finding other end uses for the waste outside of the textile value chain. One example is with the Greenful Group (Greenful.com), where textile waste is used to make strong, high-performing construction panels. Only by working outside of industry boundaries can real long-term recycling solutions be found for all the textile waste in the world. At Greenful, we welcome such collaboration and seek to work in partnership with the textile and clothing industry. Only through multi-industry partnerships can we significantly reduce the impact of textile waste on our environment.